Welcome to the Public Classroom….

Image credit: Charles Willson Peale, “The Artist in His Museum” (1822; Joseph Harrison, Jr. Collection, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts).

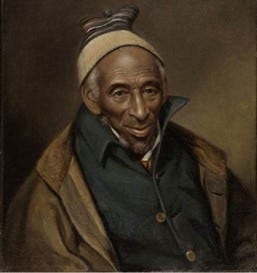

In his old age, the American painter Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827) invited the public to view his work. It was 1822 in the new nation, just 48 years since the declaring of independence. Most leaders, including sitting President James Monroe, had served in the American Revolution. At age 32, Peale had enlisted in the Continental Army. Peale is best known for his portraits of American founders including one of Thomas Jefferson from 1776 and several of George Washington. In 1819, toward the end of his life, Peale painted a portrait of Yarrow Mamout.

Mamout was an Islamic man born in Guinea, West Africa, and an ex-slave living in the District of Columbia with his own house and, Peale reports, ownership of some “Bank stock.”

In his early 80s himself, Peale used the social media of his time to paint his self-portrait in his “cabinet of curiosities,” housed in Independence Hall, Philadelphia, where the Declaration of Independence had been signed during the height of the Revolution. As with the opening of a play, Peale holds a curtain up to display the familiar and the strange from his lifetime of learning.

Like Peale, this page invites you to peek behind the curtain about what makes America tick. Bring your curiosity and your questions, your enthusiasm for American ways and your critiques.

Browse this page and more to get started…

About the Author- Paul Croce

Historian, Culture Watcher, and Curator of the Public Classroom.

Stories from the past can turn disagreements from obstacles into opportunities.

This webpage displays some of the curiosities of modern culture and politics. As a historian, I have dedicated my career to scouting for little-known stories and presenting new dimensions about familiar parts of life—in other words, making the strange familiar and the familiar strange in our often-troubling world.

As I reach toward the end of my own career teaching and writing about historical trends, especially in the United States, I now bring these parts of my vocation together, with academic insights presented briefly for the public classroom.

I have been teaching American history at Stetson University, in DeLand, Florida, since the late 1980s, and I’ve written two books and over a hundred scholarly articles, chapters, and reviews.

PublicClassroom.Substack.com is a free public service. In developing this page, I have been able to give back to the people and contexts that helped me become a professor, a job that’s allowed me to be paid to learn.

The thinking for this webpage began before the digital age, when I didn’t know much about American culture but assumed a lot. On leaving the country at age 20, I stopped taking American culture for granted. As an undergraduate exchange student in Britain, I met America again for the first time. On looking back to my native turf, I thought … The US is a place with a lot of power and influence, and with a lot of puzzlements; I want to learn more….

After earning my undergrad degree, cum laude, in Political Theory and History from Georgetown University, and my Ph.D. in American Civilization from Brown University, the miracle of the academic marketplace landed me in the American Studies Program of this small college dedicated to general education, really the kind of learning I aim for on this webpage but now not just for college-age students but for the public beyond college walls.

My own children have also contributed to the development of this webpage. To my impulses for elaboration in detail, their puzzled looks provided valuable lessons in concision, and their warnings about too much “complexifying” encouraged clarity. (Thanks, Elizabeth and Peter!) I call this the “Goldilocks Approach” of the Public Classroom.

My own deep academic dives have focused on science, religion, and William James (1842-1910), the founder of American psychology, popularizer and refiner of pragmatic philosophizing, keen observer and theorist of religious experiences, and advocate for the power of public discussions to address shortcomings in social justice. James offers continuing wisdom for our time in moving beyond both pessimism (that’s suggested by a lot of bleak facts) and optimism (blooming from idealistic visions) in favor of what he calls meliorism. Because “The world…is what we make of it,” how can we improve or ameliorate the conditions around us? No one of us can wholly solve problems on our own, but can we make our settings better? As my father would say, Leave things a little better than the way you found them.

I am particularly dedicated to learning from contrasting opinions, ideologies, philosophies, and beliefs, and that is a central theme in a lot of my writing. In our angry times, that’s swimming upstream—there’s a lot of fighting these days! Reason to stop trying to listen across differences? Fuhgeddaboudit! These fraught times present an opportunity. I perceive that the anger and the fighting can only satisfy in the short term; more enduring progress comes with learning across disagreements. James serves as a good example. His writings offer suggestions for building bridges in our time between academia and the public—and across our polarized divides.

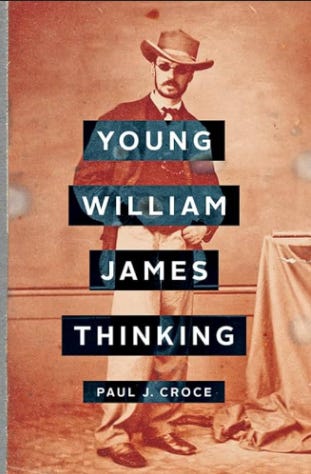

James provides a model for a lot of my work, and I’ve done my homework on him. I have served as President of the William James Society, with Harvard’s Houghton Library I organized a symposium on the centennial of his death, “In the Footsteps of William James,” and I’ve written Science and Religion in the Era of William James: Eclipse of Certainty, 1820-1880 (University of North Carolina Press, 1995); and Young William James Thinking (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018). A central finding of my research is that James turned his youthful troubles and indecisions into opportunities to learn and to remain open to contrasting perspectives, which shaped his contributions to many fields—contrasting views as sources of creativity.

Those opportunities to learn about the contexts driving different perspectives and about the resulting ideologies—the good, the bad, and the works in progress—have motivated my approaches to teaching in the academic classroom and now also for the public classroom. With Public Classroom, I am not seeking political power or influence. I am a historian—not much power in that! But in my position as a teacher and as a learner, as a reader and as a writer, I can share stories and explanations about the American past and present, and the US in relation to the rest of the world. And these stories and explanations may provide clarity about how we’ve arrived at some of our achievements and our troubles. That’s not politics but that is some of the GPS for our political thoughts and actions. These can provide ways for listeners and readers to generate healthier futures for themselves, for their relations with each other, and for our political life together.

Visit more of PublicClassoom.Substack.com to find stories about American culture with an emphasis on learning across differences. These can add new twists for your understanding of life in these United States, how we’ve gotten to our present setting and how to prepare for what’s next.

For a description of the Public Classroom goal, see this essay: